Chapter 7 Alternative Approaches to Achieving Competitive Advantage

LEARNING OBJECTIVES 1. Explain the concept of competitive advantage. |

1. Competitive Advantage

1.1 Two factors affecting profitability

1.1.1 Porter argued that two factors affect the profitability of companies:

(a) industry structure and competition within the industry: he used the Five Forces model to explain the factors affecting competition.

(b) at the level of the individual company, achieving a sustainable competitive advantage. Sustainable competitive advantage is achieved by creating value for customers.

1.2 Value and competitive advantage

1.2.1 Companies and other business entities in a competitive market should seek to gain an advantage over their competitors. As explained in earlier chapters, competitive advantage means doing something better than competitors, and offering customers better value.

1.2.2 Having some competitive advantage over rival firms is essential. Without it, there is no reason why customers should buy the company’s products instead of the products of a competitor.

1.2.3 Essentially, competitive advantage arises from the customers’ perception of value for money. Value was explained in the chapter on the value chain and value networks. The key point to understand is that value comes from:

(a) a low price, or

(b) features of the product (or the way it is made available to customers) – both real and imagined – that make the customer willing to pay a higher price, or

(c) a combination of price and product features that gives ‘best value’ to a group of customers in the market.

1.2.4 Note that value is determined by the perception or opinion of customers. A combination of price and product features that gives ‘best value’ to one customer might not give ‘best value’ to another, because the customers have different perceptions of value.

1.3 Selecting business strategies for competitive advantage

1.3.1 Since there are different perceptions of value, companies have to make a strategic decision about how they will try to offer value and gain competitive advantage.

(a) Companies decide their corporate strategy, and the combination or portfolio of businesses (‘product-markets’) they want to be in.

(b) They must then select one or more business strategies that will enable them to succeed in their chosen product-markets.

2. Strategic Clock

2.1 Purpose of the strategic clock

2.1.1 The two key factors in providing value to customers are the price of the product or service and the benefits that customers believe the product or service provides. Competitive advantage comes from offering an attractive combination of price and perceived benefits.

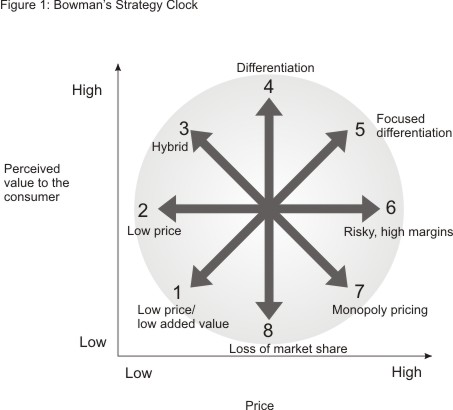

2.1.2 The strategic clock was suggested by Bowman (1996) as a way of looking at combinations of price and perceived benefits. Companies should consider which combination of the two they should try to offer, although to do this they must also understand the perception of customers about the benefits that the product or service provides.

2.1.3 Companies can also use the strategic clock to assess the business strategies of competitors, and the combination of price and benefits that they are offering.

2.2 Drawing a strategic clock

2.2.1 The strategic clock has two dimensions: price and perceived benefits. Price can be shown on a scale ranging from ‘low’ to ‘high’. Similarly, perceived benefits can be shown on a scale from ‘low’ to ‘high’.

2.2.2 The ‘clock’ consists of a series of business strategies. Each business strategy is shown as the hand of a clock, pointing in the direction of a combination of price and perceived benefits. Each business strategy has a different combination of price and perceived benefits, where customers have different requirements in terms of value for money.

2.2.3 The different positions on the clock also represent a set of generic business strategies for achieving competitive advantage.

2.2.4 There can be any number of different business strategies, each with its own combination of price and perceived benefits. However, the different business strategies can be grouped into:

(a) five business strategies that might enable a firm to gain a competitive advantage, and

(b) strategies that will fail because they cannot provide competitive advantage.

2.3 Using a strategic clock

2.3.1 A strategic clock can be used to consider different business strategies for gaining competitive advantage, based on providing a combination of price and perceived benefits.

2.3.2 In your examination, you might be given a case study or scenario and asked to suggest a suitable business strategy for a company. The strategic clock might be a useful basis for making an analysis – looking at the business strategies of competitors, and what a company must do to find an appropriate combination of price and perceived benefits that it should offer to customers.

2.3.3 The five broad groups of business strategy that might succeed are:

(a) a ‘no frills’ strategy (position 1 on the clock)

(b) a low price strategy (position 2)

(c) a differentiation strategy (position 4)

(d) a hybrid strategy (position 3)

(e) a focused differentiation strategy (position 5)

(a) No frills strategy: Position 1

2.3.4 A ‘no frills strategy’ is to offer a product or service at a low price and with low perceived benefits. It should attract customers who are price-conscious, and are happy to buy a basic product at the lowest possible price.

2.3.5 This strategy has been used by low-cost airlines, which offer a basic service for a low price.

2.3.6 With a ‘no frills’ strategy, customers understand that they are buying a product or service that gives them fewer benefits than rival products or services in the market.

(b) Low price strategy: Position 2

2.3.7 With a ‘low price’ strategy, customers perceive that the product or service gives average or normal benefits. It is not regarded as a low-quality product. The price, however, is low compared with similar products in the market.

2.3.8 Only the lowest-cost producer in the market can implement this business strategy successfully. If a company that is not the least-cost producer tries to implement a ‘low price strategy’ there will be a continual threat that the least-cost producer will copy the same strategy, and offer prices that are even lower. Only the least-cost producer could win such a price war.

2.3.9 However, a ‘low price’ strategy can be applied in segments or sections of the market. For example, supermarkets offer their ‘own brand’ products at prices that are lower than similar branded goods. Customers shopping in a supermarket might buy the low-price own-brand goods rather than higher-priced branded goods (which might be perceived as offering more benefits to customers).

(c) Differentiation strategy: Position 4

2.3.10 A differentiation strategy is based on making a product or service appear to offer more benefits than rival products or services. Companies try to differentiate their own particular products – make them seem different. There are various ways in which differentiation can be achieved: products or services might have different features, so that rival products do not offer exactly the same benefits. Companies might also promote the perception that their products or services are much better in quality.

2.3.11 In the strategic clock a strategy of differentiation involves charging average prices for the product or service, or prices that are perhaps only slightly higher than average. The strategy does not involve charging prices that are very much higher than average. Customers therefore believe that they are getting more benefits for every $1 they spend.

(d) Hybrid strategy: Position 3

2.3.12 A hybrid strategy involves selling a product or service that combines:

(a) higher-than average benefits to customers, and

(b) a below-average selling price.

2.3.13 To be successful, this business strategy requires low-cost production and also the ability to provide larger benefits. It tries to achieve a mix between a low price strategy and a differentiation strategy.

(e) Focused differentiation strategy: Position 5

2.3.14 A focused differentiation strategy is to sell a product that offers above-average benefits for a higher-than-average price. Products in this category are often strongly branded as premium products so that their high price can be justified. Gourmet restaurants and Ferrari sports cars are examples of products sold using this business strategy.

(f) Business strategies on the clock that will fail

2.3.15 The diagram of the strategic clock shown above indicates some business strategies that will not succeed, because they do not enable the company to gain a competitive advantage. There are other strategies that competitors might adopt that will be more successful.

2.3.16 Strategies in the area that could be described as ‘three o’clock’ to ‘six o’clock’ on the strategic clock are clearly inferior to strategies on other parts of the clock.

(a) Products with perceived benefits that are below-average cannot be sold successfully when there are lower-priced products offering the same perceived benefits. Customers will not pay more for products that, in their opinion, give them nothing extra.

(b) Similarly products cannot be sold successfully at an above-average price when they have below-average perceived benefits. Customers can pay similar prices for products offering more benefits (which will be sold by companies pursuing a focused differentiation strategy).

2.4 Conclusion: strategic clock

2.4.1 Each business strategy is ‘market facing’, which means that it aims to meet the needs of customers, or a large proportion of potential customers in the market. It is therefore very important to understand the critical success factors (CSFs) for each position on the clock. In particular, what exactly does ‘above average’ benefits mean?

2.4.2 A useful exercise is to think about any product or service with which you are familiar, and a company that provides the product or service. The market should be competitive. Then try to describe the business strategy that the company has for its product or service, using the strategic clock as a basis for analysing business strategies.

2.4.3 Remember that the benefits of a product or service do not have to be different product design or different product quality. Other features of a product or service could give them better value in the opinion of customers, such as fast speed of delivery, availability in stock, convenience of purchase, a better after-sales service or a product guarantee. Benefits do not have to be real: what matters is whether customers believe that a product offers more benefits. Branding and advertising can create extra benefit in the perception of customers.

3. Cost leadership, differentiation and lock-in strategies

3.1 Porter’s generic strategies for competitive advantage

3.1.1 Porter has suggested three strategies for sustaining competitive advantage over rival firms and their products or services. These strategies, which are similar to some shown on a strategic clock, are:

(a) a cost leadership strategy

(b) a differentiation strategy

(c) a focus strategy

3.1.2 Porter argues that sustainable competitive advantage is achieved by offering customers a ‘value proposition’. This is a set of benefits that the product or service will provide, that are different from those that any competitors offer. A value proposition can be created in two ways:

(a) Operational effectiveness. This means doing the same things better than competitors, and so providing the same goods or services at a lower cost. Through lower costs, sustainable competitive advantage can be gained through lower selling prices.

(b) Strategic positioning. Strategic positioning means doing things differently from competitors, so that the company offers something unique to customers, so that customers will be prepared to pay a higher price to acquire the unique value combination that the product or service offers.

3.1.3 Operational effectiveness provides the basis for a cost leadership strategy and strategic positioning provides the basis for a differentiation strategy.

3.2 Cost leadership strategy

3.2.1 Cost leadership means being the lowest-cost producer in the market. The least-cost producer is able to compete effectively on price, by offering its products at a lower price than rival products. It can sell its products more cheaply than competitors and still make a profit.

3.2.2 Companies with a cost leadership strategy must have excellent systems of cost control and should continually plan for further cost reductions (in order to remain the cost leader in the market). The source of their competitive advantage is low cost and they must never lose sight of this fact.

3.2.3 In general, the cost leader in a market is a large company, because large companies can benefit from economies of scale that smaller companies are unable to achieve.

3.2.4 The success of a cost leadership strategy is based on offering products at the lowest price, which means that in order to make a reasonable profit the company must sell large quantities of the product. Total profits usually come from selling large volumes at a low profit margin per unit.

3.2.5 A cost leadership strategy is similar to a ‘low price’ strategy or a ‘no frills’ strategy on the strategic clock.

3.3 Differentiation strategy

3.3.1 A differentiation strategy has been explained in relation to the strategic clock. For Porter (and for writers on marketing management) differentiation means making a product different from rival products in a way that customers can recognise.

3.3.2 Customers might be willing to pay a higher price for the product, because they value its different features. Companies pursuing a differentiation strategy need to offer products and services that are perceived as better or more suitable than those of their competitors. To deliver better products and services usually requires investment and innovation.

3.3.3 Products may be divided into three categories:

(a) Breakthrough products offer a radical performance advantage over competition, perhaps at a drastically lower price (e.g. float glass, developed by Pilkington).

(b) Improved products are not radically different from their competition but are obviously superior in terms of better performance at a competitive price (e.g. microchips).

(c) Competitive products derive their appeal from a particular compromise of cost and performance. For example, cars are not all sold at rock-bottom prices, nor do they all provide immaculate (完美的) comfort and performance. They compete with each other by trying to offer a more attractive compromise than rival models.

3.3.4 How to differentiate?

(a) Build up a brand image, e.g. Pepsi’s blue cans are supposed to offer different ‘psychic benefits’ to Coke’s red ones.

(b) Give the product special features to make it stand out, e.g. Russell Hobb’s Millennium kettle incorporated a new kind of element, which boils water faster.

(c) Exploit other activities of the value chain, e.g. quality of after-sales service or speed of delivery.

3.3.5 Companies with a differentiation strategy cannot ignore cost. They should keep costs under control and try to reduce costs, so that they can offer more value to customers and retain their competitive advantage. However, they are not trying to be the least-cost producers. It more important for a successful differentiation strategy that products should give more benefits to the customer, even if this means having to spend more to deliver the product.

3.4 Focus (or niche) strategy

3.4.1 A cost leadership strategy and a differentiation strategy can be pursued in a market that is not segmented.

3.4.2 However, many consumer markets are segmented, and companies might select one or more particular segments as target markets for their product. This is a focus strategy – concentrating on selling the product to a particular segment of the market and to a particular type of customer.

3.4.3 Within a market segment, a business entity might seek competitive advantage through:

(a) cost leadership within the market segment, or

(b) product differentiation within the market segment.

3.4.4 |

Example 1 |

|

In the market for manufacturing and selling soap, one or two companies might pursue a strategy of being the cost leader in the market, and offer their standard products to customers at the lowest prices. Other producers of soap might pursue a differentiation strategy, and promote the superior quality of their products, for example by including ingredients that are better for the skin or provide a more attractive aroma (氣味). Some producers of soap might focus on a particular market segment, such as the market for liquid soap. Within this market segment, firms might either seek to be the least-cost producers or to offer a differentiated liquid soap product. |

3.4.5 |

Example 2 |

||||||

|

Porter’s generic strategies can be used to suggest how airline companies seek competitive advantage. These are suggestions.

|

3.4.6 |

Example 3 |

|

The market in the UK for holiday companies is another example of a segmented market, in which different companies pursue a cost leadership, differentiation or focus strategy. The main market for holiday companies is probably the package holidays market, where a small number of competitors attempt to be the cost leader, although differences in some features of holiday packages mean that a competitive advantage can be gained from low prices, even if these are not the lowest prices in the market. Some companies offer a package holiday at a higher price, but with better quality accommodation or additional benefits such as onsite pastimes and entertainment. There are a number of market segments, such as fly-drive holidays [(包含搭乘飛機和租用汽車的)陸空旅遊假期], city breaks and adventure holidays. Within each market segment competitors seek to be the cost leader or differentiate their products. |

3.5 Target market

3.5.1 An entity must decide which markets or market segments it should target. It must:

(a) identify the total market for the products or services that it sells

(b) recognise the ways in which the market is or might be segmented

(c) decide whether to sell its products to all customers in the market

(d) decide whether to try to be the market leader, or whether to pursue a differentiation strategy

(e) if it chooses a segmentation strategy (focus strategy), select the segments that it will target with its product

(f) within the targeted market segment (or segments), decide whether to try to be the market leader or whether to pursue a differentiation strategy.

3.6 Leaders, followers, challengers and nichers

3.6.1 A business entity can be classified as a leader, follower, challenger or nicher in its markets.

(a) The leader is the entity that sells most products in the market. Examples are Microsoft for PC operating software and Coca-Cola for cola drinks.

(b) A challenger is an entity that is not the market leader, but wants to take over as the market leader.

(c) A follower is an entity that does not have any ambition to be the market leader, and so follows the strategic lead provided by the market leader (or challenger). A follower will try to differentiate its product.

(d) A nicher is an entity that targets a particular market segment or market niche for its product, and does not have any strategic ambition to gain a position in the larger market.

3.7 Product positioning

3.7.1 The concept of product positioning is now widely used in marketing. The idea originated with Ries and Trout in the late 1960s.

3.7.2 They defined product positioning as the concept of the product in the mind of the customer. Advertising is an important factor in creating product position.

3.7.3 Ries and Trout argued that consumers receive vast amounts of advertising information, but they will only accept the messages that are consistent with their existing knowledge and experience.

3.7.4 They also argued that the best product position to achieve in the mind of consumers is the position of number 1. The market leader dominates the market for many products and services, and customers will often buy a product because it is the number 1.

(a) Being the number 1

3.7.5 When an entity is the market leader, it should want to maintain its market leadership. To do this, it needs to maintain its position as number 1 in the mind of consumers.

(a) The most effective way of becoming number 1 in the mind of consumers is to be first into the market at the beginning of the product’s life cycle.

(b) If this is not possible, an entity needs to create a new image for its product, that will enable it to take over as the perceived number 1.

(b) Being the number 2

3.7.6 When an entity is only the number 2 in its market, customers will know this. Unless the entity wants to challenge for the position of number 1, it must do what it can to win customers from its position as number 2. Advertising can help.

3.7.7 |

Example 4 |

|

In the US, Avis has been the number 2 car-hire company, and Hertz the number 1. Avis achieved a position as an attractive number 2 by recognising its number 2 position, but offering something better than the number 1. Its successful advertising message was: ‘Avis is only the number 2 in rent-a-car, so why go with us? We try harder.’ (It is not clear what trying harder means, but this did not matter!) Pepsi promoted its 7-Up soft drink against market leader Coca-Cola by advertising it as the ‘Uncola’. This recognised that it was not the number one soft drink, but offered customers the attraction of not being cola. |

(c) Product positioning for followers and nichers

3.7.8 Ries and Trout argued that entities that are not the number 1 in their market should try to find a way of being number 1 in a particular way. It is much better to be seen as the number 1 in a market segment (or in a special way) than the number 5 in the market as a whole.

3.7.9 To create a product position of number 1 in the mind of customers, entities might devise various marketing strategies.

3.7.10 The approach recommended by Ries and Trout is to be the number 1 for a particular type of customer, such as the number 1 product for women or the number 1 product for professional businessmen. For example:

(a) a newspaper or magazine might claim to be the number 1 choice for investment bankers or investors

(b) a local radio station might claim to be the number 1 commercial station in its geographical area, or the number 1 station for a particular type of music

(c) Apple Mac PCs were not the number 1 make of personal computer, but it was marketed as the number 1 PC for graphic designers.

3.8 Lock-in strategy

3.8.1 A lock-in strategy is another approach to gaining and keeping competitive advantage. The idea of ‘lock-in’ is that when a customer has made an initial decision to purchase a company’s product, it is committed to making more purchases from the same company in the future. The customer is ‘locked in’ to the supplier and the supplier’s products.

3.8.2 |

Example 5 |

|

Lock-in strategies are fairly common in the IT industry. Microsoft has successfully locked in many customers to its software products. Customers would find it difficult to switch to personal computers that do not have a Microsoft operating system or do not include some of the widely-used application packages such as Word and Excel. Apple Computers adopted a lock-in strategy for digital downloading of music from the internet. Its iTunes service cannot (currently) be used on non-Apple MP3 players or on most mobile telephones. Customers buying an Apple iPod are currently locked in to buying digital downloads from Apple. |

3.8.3 A successful lock-in strategy often depends on becoming the industry ‘leader’ or provider of the standard product to the industry (such as the Microsoft operating systems for PCs). Once an organisation has become the industry standard, it is very difficult for other suppliers to break into the market. Indeed, market standard positions tend to be reinforced as time goes on as more and more people turn to that supplier.

3.8.4 Lock-in tends to be achieved early in a product’s life cycle when the new supplier achieves an unassailable (攻不破的) lead.

3.9 Strategies in conditions of hypercompetition

3.9.1 Cost advantage is much more difficult to sustain when there is hypercompetition in the market. Hypercompetition occurs when ‘the frequency, boldness and aggressiveness of dynamic moves by competitors create conditions of consistent disequilibrium and change.’

3.9.2 In a market where competitive conditions are more stable, business strategy is concerned with building and sustaining competitive advantage.

3.9.3 In a hypercompetitive environment it is much more difficult to establish sustained competitive advantage through either cost leadership or differentiation, because any competitive advantage that is gained will be temporary. Competitors in a hypercompetitive environment continually look for ways of competing in different ways, so that no company can sustain competitive advantage for long using the same basis for achieving its advantage.

3.9.4 Product and services that were once successful might not be relevant for long. Long-term competitive advantage is achieved only through making a continual sequence of short-term competitive initiatives.

3.9.5 Strategies that might be pursued in a hypercompetitive market are as follows:

(a) Shorter product life cycles. Seek to introduce new improved products quickly, to compete against established products of competitors. Introducing a ‘better’ product might allow a company to gain market share, although this advantage will only last until another competitor introduces a new, improved product that is even better.

(b) Imitate competitors. Imitating competitors might remove the competitive advantage that the competitors currently enjoys.

(c) Prevent a competitor gaining a strong initial position by responding quickly.

(d) Concentrate on small market segments that might be overlooked by competitors. Eventually, the market might be divided into many small market segments.

(e) Unpredictability. Companies should continually strive for radical solutions. Be prepared to abandon current approaches.

(f) In some situations, it might be possible to compete by building alliances with some smaller competitors to compete with larger companies that are financially stronger and currently are the market leaders.

4. Collaboration

4.1 The nature of collaboration

4.1.1 In a competitive market, companies need to achieve a competitive advantage over competitors in order to succeed (and survive). In some situations, companies might be able to achieve competitive advantage through collaboration with:

(a) suppliers or customers in the value network/value system

(b) other business entities in the value network

(c) some other competitors.

4.1.2 Collaboration with suppliers and customers can create additional value, in areas such as:

(a) product design: suppliers and customers might collaborate to improve the product design, by improving the design of product components or providing better raw materials

(b) delivery times: suppliers and customers might collaborate to improve the reliability and speed of delivery, for example through a just-in-time purchasing arrangement.

4.2 Collaboration and strategic alliances

4.2.1 Another way of trying to increase competitive advantage is to collaborate with other companies in the same industry, who might possibly be regarded as competitors. One form of collaboration is to create a strategic alliance.

4.2.2 A strategic alliance is an arrangement in which a number of separate companies share their resources and activities to pursue a joint strategy. By collaborating, all the companies in the alliance are able to offer a better product or service to their customers.

4.2.3 |

Example 6 |

|

Examples of strategic alliances are in the airline industry where groups of airlines might form alliances in order to offer travellers a better selection of routes and facilities than any single airline could offer on its own. Strategic alliances have included Oneworld (British Airways, American Airlines and others) and Star Alliance (Lufthansa, BMI and others). A strategic alliance of airlines enables the combined alliance to offer customers the ability to arrange journeys by air to and from most parts of the world with a single booking; however, the airlines do not compete on most routes. A UK-based international airline might want to offer its customers linked flights from anywhere in the UK to anywhere in the US. Since it does not have a US flight network, it might enter into a strategic alliance with a domestic US airline. As a result of the alliance, it expects to be in a better position to compete against larger US airlines for transatlantic air traffic. A US domestic airline might want to offer its customers an all-in-one flight service from anywhere in the US to the UK. It can achieve this aim by forming a strategic alliance with the UK airline. For example, a customer in the UK wanting to arrange a flight to a city in the US not serviced by British Airways might be able to book the journey through British Airways: the customer would then fly to the US on British Airways to New York and then switch to American Airlines for onward travel to the US city destination. |

4.3 Collaboration and joint ventures

4.3.1 A joint venture is a formal venture by two or more separate entities to develop a business or an activity jointly. Many joint ventures are established in the form of a separate company which is jointly owned by the joint venture partners. No single partner being able to dominate and dictate the way that the company is run.

4.3.2 Joint ventures are frequently used for investing in a new business venture where:

(a) there is considerable risk

(b) large amounts of capital are needed

(c) a mix of skills is essential.

4.3.3 The joint venture allows the business risk and financing to be shared by the joint venture partners. The partners might be companies that compete in some markets of the world, but have agreed to collaborate in a particular venture. Alternatively the joint venture partners might be companies in different markets, and do not compete with each other directly; however each partner brings special skills to the venture that will help to give it a competitive advantage.

4.3.4 When multinational companies are seeking to expand by investing in a different country, they might seek to do so by establishing a joint venture with a local company. There are several advantages in entering a foreign market in an alliance with a ‘local’ company.

(a) It might be a legal requirement for foreign companies setting up business in the country to operate as a joint venture with a local company.

(b) The local company management should have a better knowledge of business conditions and practices in the country.

(c) It is probably easier to succeed by forming an alliance with a local company than in competition with local companies. For example, the government might be a major customer, and it might have a policy of favouring domestic companies when it makes its purchase decisions.

(d) The local company might already have customers to which the new joint venture can sell its products.

4.3.5 Difficulties can arise with joint ventures, and lead to the eventual break-up of the partnership. This can happen when:

(a) one joint venture partner is perceived (by the other partners) not to be contributing adequately

(b) one joint venture partner wants to withdraw from the venture, or

(c) the joint-venture companies start to compete with each other instead of collaborating.

4.4 Franchising

4.4.1 Some business entities have been able to grow through franchising. This is another form of collaboration. The basic idea of a franchise is that a company develops a product with the following features:

(a) It is a standard product (or range of products), delivered to customers in a standard way.

(b) It has brand recognition, achieved through advertising and other sales promotion.

(c) Systems for delivering the product to customers are standardised (using standard equipment, and standard work practices.

4.4.2 |

Example 7 |

|

The most well known examples of franchise operations are some of the fast-food restaurant chains, such as McDonalds. The company that originates the product, the franchisor, protects its patent rights or intellectual property rights over the product. It then sells the concept to franchisees who pay for the right to open their own store and sell the branded product. The franchisor supplies the product ‘design’ and the right to sell the product. It also provides a centralised marketing service, which includes extensive advertising and brand promotion. It also supplies other support services, such as business advice to franchisees. The franchisee pays for the franchise, and in addition pays a royalty based on the value of its sales or the size of its profits. |

4.4.3 By buying into a successful franchise, a franchisee suffers much less risk than would be experienced setting up a business from scratch and can benefit from extensive marketing by the franchisor.

4.4.4 The franchisor receives a constant inflow of cash from new franchisees, as the operation expands, and is therefore able to grow by selling its business concept to a large number of other businesses, sometimes worldwide. Additionally, their head office is kept small because there is considerable delegation of day-to-day management to the franchisee.

4.4.5 However, the franchisor will always want to protect its brand name and to present a consistent appearance to its customers. This means that franchise agreements have very extensive rules governing franchisees’ behaviour and they will also supply the products. Many franchisees find these rules and the monopoly supply of products very restrictive and frustrating.

4.5 Licensing

4.5.1 In a typical licensing agreement, a licensee is given permission by the licenser to make goods, normally making use of a patented process, and to use the appropriate trademark on those goods. In return the licenser receives a royalty. The licensee is exposed to relatively little risk and goods can be made wherever the licensee is located.

4.6 Possible problems with collaboration: restricting competition

4.6.1 The purpose of collaboration should be to gain competitive advantage in a market. However, it should not seek to create unfair restrictions on competition.

4.6.2 Governments in countries with advanced economies are generally in favour of ‘free’ competition in their national markets (and in international trade), although there are many exceptions to this general rule. When it has a policy of encouraging competition in markets, a government will seek to discourage actions by companies that will distort or reduce competition in their industry and markets. They might do this by making some forms of anti-competitive behaviour illegal.

4.6.3 In the UK, the government seeks to ensure that there is sufficient competition in domestic markets so that consumers get a ‘fair deal’. Some industries have special regulatory bodies, whose responsibilities include ensuring that the consumer is protected. For industries generally, the Office of Fair Trading is responsible for identifying cases where fair competition might be at risk, and referring cases to a Competition Commission for investigation.

4.6.4 The UK’s Competition Commission might be asked to investigate:

(a) a market, where the Office of Fair Trading suspects that competition is being prevented or restricted by anti-competitive behaviour

(b) a proposed merger or takeover (or merger that has already occurred), where it is suspected that a consequence of the merger will be a significant reduction in competition

(c) competition in a regulated industry, such as electricity, gas, water, telecommunications, postal services, broadcasting, airports and air traffic.

4.6.5 Cartel

A cartel is an arrangement between the rival firms in an industry to operate the same policies on pricing. By operating a price cartel, the firms are able to charge higher prices than if they competed with each other, and as a result make higher profits. Provided that the cartel includes all the firms in the industry (or at least all the major firms), they are able to exercise supplier power.

Price cartels are often illegal within a country, although an example of a successful major price cartel is the powerful Organisation of Oil Producing Countries (OPEC).

Question 1 Phase 1 (1965–1988) Hein also developed a high public profile. He dressed unconventionally and performed a number of outrageous stunts that publicised his company. He also encouraged the managers of his stores to be equally outrageous. He rewarded their individuality with high salaries, generous bonus schemes and autonomy. Many of the shops were extremely successful, making their managers (and some of their staff) relatively wealthy people. However, by 1980 the profitability of the Rock Bottom shops began to decline significantly. Direct competitors using a similar approach had emerged, including specialist sections in the large general stores that had initially failed to react to the challenge of Rock Bottom. The buying public now expected its electrical products to be cheap and reliable. Hein himself became less flamboyant and toned down his appearance and actions to satisfy the banks who were becoming an increasingly important source of the finance required to expand and support his chain of shops. Phase 2 (1989–2002) Phase 3 (2003–2008) Required: (a) Analyse the reasons for Rock Bottom’s success or failure in each of the three phases identified in the scenario. Evaluate how Rick Hein’s leadership style contributed to the success or failure of each phase. (18 marks) Explain the key factors that would have made franchising Rock Bottom feasible in 1988, but would have made it ‘unlikely to be successful’ in 2007. (7 marks) |

Source: https://hkiaatevening.yolasite.com/resources/P3BANotes/Ch7-AlternativeApproachCompAdv.doc

Web site to visit: https://hkiaatevening.yolasite.com

Author of the text: indicated on the source document of the above text

If you are the author of the text above and you not agree to share your knowledge for teaching, research, scholarship (for fair use as indicated in the United States copyrigh low) please send us an e-mail and we will remove your text quickly. Fair use is a limitation and exception to the exclusive right granted by copyright law to the author of a creative work. In United States copyright law, fair use is a doctrine that permits limited use of copyrighted material without acquiring permission from the rights holders. Examples of fair use include commentary, search engines, criticism, news reporting, research, teaching, library archiving and scholarship. It provides for the legal, unlicensed citation or incorporation of copyrighted material in another author's work under a four-factor balancing test. (source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fair_use)

The information of medicine and health contained in the site are of a general nature and purpose which is purely informative and for this reason may not replace in any case, the council of a doctor or a qualified entity legally to the profession.

The texts are the property of their respective authors and we thank them for giving us the opportunity to share for free to students, teachers and users of the Web their texts will used only for illustrative educational and scientific purposes only.

All the information in our site are given for nonprofit educational purposes