International Reconciliation in the Postwar Era, 1945-2005:

A Comparative Study of Japan-ROK and Franco-German Relations*

Yangmo Ku

Under what conditions do sets of two former adversary states with deeply rooted historical animosity try to reconcile with each other? When they seek for bilateral reconciliation, why do they show significantly different outcomes in the degree of reconciliation? France and Germany were historical antagonists that fought three catastrophic wars – the France-Prussia war, and World Wars I and II – during the period of 1870-1945. In the postwar era, however, their antagonism and hostility dramatically evolved into the establishment of mutual partnership and cooperation. Unlike the Franco-German case, Japan-ROK relations still remain frigid due to mistrust and enmity, although sixty-three years have passed since Korea’s liberation from Japanese colonial rule from 1910 to 1945. This article argues that in both cases, the motives for reconciliation were mainly derived from realpolitik concerns such as security and economy. Structural conditions also affected the initiation of international reconciliation. Nonetheless, it was the dynamics of political leaders and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) that played central roles in differentiating the reconciliation processes and outcomes in the two dyadic relationships.

Key words: International reconciliation, Japan-ROK relations, Franco-German relations

Introduction

Under what conditions do sets of two former adversary states with deeply rooted historical animosity try to reconcile with each other? When they seek for bilateral reconciliation, why do they show significantly different outcomes in the degree of reconciliation? This article addresses these questions through examining the two dyadic cases—postwar Japan and the Republic of Korea (hereafter ROK or South Korea) and Franco-German relations. Although the two sets of dyads share deep-seated historical antagonism, France and Germany reached a far deeper stage of reconciliation than Japan and the ROK during the postwar era.

France and Germany were historical antagonists that fought three catastrophic wars—the France-Prussia war and two World Wars—during the period of 1870-1945. Particularly, France’s sudden defeat during World War II by the Nazi invasion in June of 1940 led to the serious humiliation of France and the persistence of harsh Nazi rule for nearly four years. In the postwar era, however, the antagonism and hostility between France and Germany dramatically evolved into the establishment of mutual partnership and cooperation. Notably important are the formation of a security alliance, the engagement in economic and political integration of the European community, the joint writing of a history textbook, and the improvement of mutual perception among two nations. The Franco-German reconciliation has thus played a key role in promoting peace and prosperity throughout Western Europe.

On the other hand, the Japan-ROK relationship progressed in a different direction during the postwar era. The origin of the historical antipathy between Japan and Korea dates back to 1592 when Japan invaded Korea. Yet the most significant root of historical enmity stems from Japan’s colonial rule over Korea for thirty-six years from 1910 to 1945. During this period, Koreans suffered under Japan’s relentless political repression, economic exploitation, attacks against Korean culture, and violations on the human rights of Koreans. Unlike the Franco-German case, Japan and South Korea followed a fluctuating path ranging from chronic antagonism to limited cooperation during the postwar era. Although sixty-three years have passed since Korea’s liberation from Japanese colonial rule, it still appears as if Japan-ROK relations remain frigid due to distrust and hostility.

This article argues that in both cases, the motives for reconciliation were mainly derived from realpolitik concerns such as security and economy. Structural conditions also affected the initiation of international reconciliation. However, it was the dynamics of political leaders and NGOs that played pivotal roles in differentiating the reconciliation processes and outcomes in the two dyadic relationships. The Franco-German case showed not only the strong joint political leadership for reconciliation, but also the vibrant activities of reconciliation-promoting NGOs during the early postwar period. Since then, France and Germany have largely maintained and nurtured their reconciled relationship on both intergovernmental and popular levels, despite some conflicts of interests. In the Japan-ROK case, on the other hand, there was no joint political leadership for reconciliation and activities of reconciliation-promoting NGOs in the early postwar era. In the later periods, the negative dynamics of political leaders and NGOs in both countries often disrupted the upgraded relationships affected by their positive dynamics.

Concept of International Reconciliation

Although there are many definitions in the previous literature of international relations, the concept of reconciliation is originally derived from biblical texts, meaning “the restoration of right relationship,” which can be termed as a state of shalom. Shalom connotes not only the absence of violence and the disappearance of hostility, revenge, and anger motivated by hatred, but also the completion of justice and mutual love. David Crocker juxtaposes reconciliation on the spectrum ranging from “thin”—e.g., former enemy parties continuing to coexist without taking active revenge – to “thick,” which entails “forgiveness, mercy, a shared comprehensive vision, mutual healing, or harmony.”

Modifying these individual or societal levels of reconciliation, Yinan He provides a systematic conceptual framework of international reconciliation embodied by two major components—stable peace and an amicable atmosphere. Stable peace, which largely pertains to the intergovernmental relationship, refers to “a condition in which even the possibility of armed conflict has been virtually eliminated,” not merely the absence of war. An amicable atmosphere, which covers the popular relationship, means that people of two former enemy states share mutual trust and/or a sense of affinity. Based on He’s conceptual framework, this article also looks into both government-to-government and people-to-people relationships in order to understand the degree of reconciliation between the former enemy states.

There are some works in international relations that directly deal with reconciliation between former adversary states. Among them, Yinan He’s dissertation seems to be one of the most theoretical and systematic analyses. She seeks to explain the success and failure of deep reconciliation by creating the theory of history mythmaking, which posits that whether historical interpretations are convergent or divergent significantly affects the degree of international reconciliation. This theory offers some explanatory reasoning why Japan and the ROK failed to enter a stage of successful reconciliation, as their historical interpretations were always divergent. However, it cannot explain the changes in the degree of reconciliation between Japan and South Korea, particularly regarding why political leaders in the two countries initiated reconciliation efforts, given unchanged historiographical divergence.

In the pre-existing literature, a variety of variables—e.g., historical perception, U.S. policies, political leaders, NGOs, and international institutions, etc.—were used to explain postwar Japan-ROK and Franco-German relations respectively. For the Japan-ROK case, however, most of the previous literature falls into the category of diplomatic histories, rather than analytical inquires. Although it offers detailed information of key events, this literature does not pay great attention to offering theoretical and systematic explanations of the relationship. Furthermore, the literature primarily focuses on a historical perception gap for explaining the unstable baseline of or the continuity in Japan-ROK relations. The historical perception approach may be useful for analyzing instances of conflict between the two countries; however, its static nature has trouble accounting for the variations—a series of ups-and-downs, particularly the cases of “ups”—in their relations.

Victor Cha’s quasi-alliance model (as a variant of realism) is an exception that goes beyond descriptive historical narratives in the literature of the Japan-ROK relationship. The model emphasizes the U.S. policies as a key causal determinant of changes in Japan-ROK bilateral behavior. The U.S. disengagement from Northeast Asia generates Japan-ROK cooperation due to their multilateral symmetric abandonment fears regarding the U.S. On the other hand, U.S. engagement in the region leads to Japan-ROK friction because of their bilateral asymmetric abandonment/entrapment fears. Despite its theoretical parsimony, his analysis overlooks the intended impact of states’ policy coordination on their bilateral relations. In terms of empirical evidence, it also fails to explain an important event, the signing of the 1965 Basic Relations Treaty between Japan and South Korea, under active U.S. engagement in the region at the time.

In explaining postwar Franco-German relations, the previous literature may be roughly classified into the following four categories: 1) historical narratives ; 2) institutional approaches ; 3) political leaders-oriented analyses ; and 4) approaches focusing on NGOs. One distinct shortcoming of the overall literature is to assume the establishment of Franco-German reconciliation without providing systematic information. And, historical narratives provide plenty of detailed information over key events; yet they often fail to analyze the relationship in a theoretical or systematic way. The NGOs-oriented approaches primarily focus on reconciliation-promoting NGOs, thereby overlooking the impact of nationalistic NGOs that work against the reconciliatory NGOs. Additionally, accounts emphasizing the nature of political leaders are a popular approach in analyzing Franco-German relations, yet they are at best descriptive and insufficient explanations.

It appears, moreover, that too much attention was paid to the role of international institutions in explaining the Franco-German cooperation (or reconciliation). Yet, the rationalist institutional approach alone is not sufficient enough to account for the degrees of reconciliation between the two countries during the postwar era. For instance, the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC)—the harbinger of Franco-German reconciliation—was established before the existence of an institutional framework. Also, the European Economic Community (EEC) was created regardless of the existing ECSC institutional framework. Additionally, there was a failure in military cooperation in the European Defense Community (EDC), the very model of a European security institution.

Alternative Approach: Political Leadership-NGOs Hypothesis

This article seeks to complement the weaknesses in the pre-existing literature by analyzing simultaneously the roles of domestic agents—i.e., political leaders and NGOs— in the reconciliation processes. Since political leaders actually govern a country on a daily basis by their policy decisions, it may be implausible to exclude their roles in explaining the changes of reconciliation degree. Yet, the initiatives taken by political leaders would not last long without NGOs’ support for their reconciliation efforts. By the same token, although NGOs can serve as catalysts to promote international reconciliation, their roles by themselves would be insufficient to have a significant impact on degrees of reconciliation if there were no political leaders’ decisive actions. Therefore, neither political leaders--nor NGOs--oriented approaches by themselves are adequate to explain the changing degree of Japan-ROK and Franco-German reconciliation in a systematic way.

Given this logic, the article presents a hypothesis: when there is a strong joint leadership for reconciliation plus greater strength of reconciliation-promoting relative to nationalistic NGOs, there will be the greatest progress toward reconciliation between former adversary states. Below is a 2x2 matrix that logically shows four possibilities in the degree of international reconciliation.

Joint Leadership NGOs’ Activities |

|

|

|

|

Latent Reconciliation |

Pro-R < Nationalistic |

|

Non-Reconciliation |

* denotes that pro-reconciliation NGOs are more vibrant than nationalistic NGOs

The first is the combination of a strong joint leadership and greater strength of reconciliation-promoting NGOs than nationalistic ones. In this case, both intergovernmental and popular reconciliation are highly likely. Second, when the two nations have a strong joint leadership but nationalistic NGOs’ activities are more vibrant than pro-reconciliation NGOs’, intergovernmental reconciliation is likely to take place. Yet, active nationalistic NGOs would often prevent the progress toward popular reconciliation. Third, when the two nations have a weak joint leadership but pro-reconciliation NGOs are more active than nationalistic NGOs, they are not likely to reconcile with each other at the intergovernmental level. However, once political leaders are determined to seek for bilateral reconciliation, the possibility of reconciliation will increase significantly in both intergovernmental and popular dimensions. Lastly, when the two nations have a weak joint leadership and nationalistic NGOs are more dynamic than reconciliation-promoting ones, they would not escape from non-reconciliation. In the next section, the validity of this approach will be tested against detailed historical facts in the processes and outcomes of postwar Japan-ROK and Franco-German reconciliation.

Diverging Pathways of Franco-German and Japan-ROK Reconciliation

Structural Conditions: To analyze different processes and outcomes of postwar Franco-German and Japan-ROK reconciliation, it is first necessary to examine structural conditions for reconciliation in the early postwar period. For the Franco-German case, the two neighbors were under relatively favorable conditions under which they could initiate bilateral reconciliation in the early 1950s. First, the two nations came to have a basic desire for peace, as they were exceedingly tired of long and devastating wars in Europe. Second, they faced overwhelming common threats from the Soviet Union, which steered them to fostering incentives for reconciliation. Third, the de-Nazification of Germany—a precondition necessary for the congruent operation of NATO—enabled France and Germany to view their reconciliation as a means of promoting their own national interests. France thus sought to maintain its international status through the development of Europe built upon Franco-German reconciliation. By the same token, Germany committed to the formation of the Franco-German axis in European integration in order to retain the trust of the international community after the atrocities of the Nazi era.

Despite the importance of the conditional factors, however, it should be too deterministic to regard them as the only reason for the diverging results in the degree of reconciliation between the two dyadic cases. In this regard, introduced is an alternative approach that analyzes the impact of the major domestic agents—i.e., political leaders and NGOs—on the initiation and sustenance of international reconciliation. For analytical and practical purposes, this article first focuses on the early postwar period of the 1950s to the mid 1960s during which France and Germany entered the stage of a successful reconciliation. Also attached is a brief explanation of the dynamics of Franco-German reconciliation during subsequent time periods.

Early Period (1950s-mid 1960s): During the late 1940s, intergovernmental and popular relationships between the two neighbors were largely filled with antagonism and suspicion. Since Germany was under the control of the Allied powers after World War II until 1949, France had important leverage to manage its relations with Germany during that period. In the hope of partitioning Germany, then controlling its economy and precluding its rearmament, France pursued a policy to place at least parts of Germany resolutely under French control, thus laying claims to Germany’s industrial centers, particularly the coal-rich region of the Saar. This French policy was a major obstacle in the early Franco-German reconciliation. There is no denying that popular feelings harbored by both nations were then unfavorable and antagonistic due to memories of traumatic wars. During this period, nonetheless, many pro-reconciliation NGOs began to take actions for initiating bilateral reconciliation between France and Germany.

The period of the 1950s-mid 1960s was a changing phase during which political leaders in France and Germany actively initiated and institutionalized their bilateral reconciliation. Given the favorable conditions already mentioned, Konrad Adenauer, the first chancellor of the newly created West Germany, and the French Foreign Minister, Robert Schuman, took the first significant step towards the Franco-German reconciliation at the intergovernmental level. When Adenauer proposed, in March 1950, the plan to build up the political union of Europe with a Franco-German pillar as its foundation, Schuman suggested an economic union for coal and steel production between France and West Germany in response to the proposal. Despite strong domestic resistance, the so-called Schuman Plan—drafted by Jean Monnet—was ratified in both countries, leading to the creation of the ECSC. This initiative resulted in the resolution of the long-festering territorial dispute entangled with the Saar region. It also spawned a striking outcome that France and Germany became one another’s best trading partners seventeen years later.

Another vital initiative taken by political leaders was the signing of the Franco-German Treaty of 1963, also known as the Elysèe treaty. In an attempt to promote French influence in Europe, French President de Gaulle proposed a confederation conducive to rendering Western Europe a political, economic, and cultural union in late 1960. Yet the Belgians and Dutch were strongly opposed to the plan because they longed for both a supranational community and one with the British in it. As a result, the project finally died in 1962. De Gallue thus pushed for closer relations with Germany alone, which resulted in the establishment of a formal agreement with Germany. However, it was not easy for the two states to sign the friendship treaty mainly because de Gaulle was vehemently opposed to British entry into the European Community (EC). His strong opposition caused Germany and other European nations to take intense and hostile reactions in the sense that a bilateral treaty with anti-U.S. and anti-British accents would be outdated and detrimental to the West as a whole. Nevertheless, Adenauer pushed for signing the treaty, which played a crucial role in sealing the Franco-German reconciliation. In this regard, the joint leadership between de Gaulle and Adenauer in the late 1950s and early 1960s contributed greatly to the Franco-German reconciliation.

The 1963 Elysèe treaty served as a key mechanism by which to institutionalize international reconciliation between the two former adversary states. It included measures to promote closer bilateral cooperation in various fields such as foreign policy, defense, education, and youth exchanges. Particularly, the treaty played a pivotal role in forging two linkage mechanisms – the requirement for regular consultation and the promotion of interaction on an interpersonal level – in order to make the Franco-German reconciliation more durable. Owing to its provisions, top officials in both states gathered on a regular basis to discuss each other’s concerns and problems. These meetings not only promoted mutual understanding among leaders but also increased the necessity of preparation in the second and third layers of the bureaucracy. Once political leadership changed, new leaders were not able to postpone consultation with their counterparts due to the fixed schedule of meetings. Furthermore, a Franco-German Youth Office created by the treaty was conducive to revitalizing youth exchanges, conferences, and reciprocal language teaching. The treaty thereby “opened and decisively shaped a historical juncture in which observers from within and outside the two countries came to commonly consider France and Germany partners and friends.”

It would not be sufficient to only emphasize the role of political leaders in accounting for the early postwar Franco-German reconciliation. A variety of NGOs also contributed to the promotion of international reconciliation between the two former enemies. Yaacov Bar-Siman-Tov contends that “NGOs can help spread the message about the importance of constructing peaceful relations, help establish cooperative and friendly relations with the past adversary, or provide economic assistance to the society members.” Particularly essential were the following three NGOs: 1) the Bureau International de Liaison et Documentation (BILD); 2) the Comite francais d’Echanges avec l’Allemagne nouvelle; and 3) the Deutsch-Franzosisches Institut at Ludwigsburg. They were not only dedicated to the elevation of Franco-German understanding through publications about contemporary affairs in both countries, but these NGOs also aimed to foster bilateral reconciliation via a continuous dialogue on current affairs. NGOs over history also played an essential role in preventing the eruption of historical disputes between France and Germany. Historians from both countries gathered for the first time in 1950 and established joint historical commissions through a series of meetings over the years, thereby making great efforts to revise textbooks and national histories. Particularly, the role of the International Textbook Institute (later, changed into the Georg Eckert Institute), established in 1951, was prominent in terms of resolving history textbook problems between France and Germany.

Consequently, both political leaders and NGOs took the leading role in the initiation and institutionalization of reconciliation between France and Germany during the early postwar period of the 1950s-mid 1960s. According to Alfred Grosser, the French view in 1944, which was “no enemy but Germany” changed into “no friend but Germany” by 1960. “59 percent of young people questioned in one French poll in 1963 gave it as their opinion that the past should be forgotten as far as Franco-German relations were concerned.” Opinion polls also indicate that by 1965 the French public considered Germany as the best friend of France. Another opinion poll, furthermore, confirms the successful Franco-German reconciliation during the early postwar period. In answer to the 1961 poll question, “In case of war, to what extent do you think you could trust (the other country) as an ally?” 57 percent of the French had confidence in the Germans and 76 percent of the Germans had confidence in the Frenchmen. In 1955, there were 38 percent and 37 percent respectively.

Late Period (after the mid-1960s): The subsequent time periods showed stable progress in Franco-German reconciliation, given the deeply embedded dynamics of political leaders and NGOs from the early postwar era. Particularly evident were the roles of the three duos—i.e., Pompidou and Brandt, Giscard and Schmidt, and Mitterrand and Kohl—who made great efforts to promote reconciliation after the joint political leadership between de Gaulle and Adenauer. They played a key role in preventing the proliferation of conflicts of interests, such as disputes over European monetary policy in the 1970s, over the US and NATO in the 1980s, and disagreements over German unification in 1989. In addition, various NGOs, including the Deutsch-Fransosischer Kreis and the Arbeitskreis der deutsch-franzosischen Gesellschaften (ADFG), served as vehicles for the Franco-German reconciliation by means of lectures, conferences, and programs for youth exchanges and the training of leaders. As a reporter describes, “Franco-German relations resemble a good marriage. Squabbles occur. The two partners talk about problems. Tempers calm, and the relationship resumes as before.” The following two claims raised by Ulrich Krotz particularly support the robustness of the Franco-German reconciliation: 1) in the wake of at least the late 1960s, leadership changes did not fundamentally undermine or lead to ruptures in the Franco-German relationship; 2) the changes of the partisan composition of French and German governments and the party coalitions also failed to cause rifts.

The two neighboring countries consistently maintained and nurtured their reconciled relationship on both intergovernmental and popular levels, based on the following evidence. The intensity of cooperation links was markedly enhanced in many spheres, including political, economic, cultural, and military-security levels. Among those increased links was the establishment of the Franco-German Cultural Council, the Franco-German Finance and Economic Council, and the Council for Common Defense and Security in 1988. As shown in Table 1, in 1993 the volume of German’s trade with France was far larger than with any other countries. In particular, the late 1980s and early 1990s witnessed the creation of the Franco-German joint brigade and the Euro-corps. Beyond semiannual summit meetings and quarterly foreign ministerial meetings, furthermore, exchanges of diplomats and civil servants became routine by the 1990s.

Table 1. Germany’s Trade with Other Countries as Percentages of German GDP (1993)

Countries |

U.S. |

Japan |

France |

Italy |

U.K. |

Percent |

1.76 |

1.57 |

6.73 |

4.99 |

3.94 |

On the popular level, furthermore, we can see a series of important results of public opinion polls to show that France and Germany entered the stage of a successful reconciliation in the early postwar period and sustained it continuously. “In 1972 the West Germans chose the French as their favorite neighbors; According to the 1973 public opinion poll, over half those questioned felt that Germany would never again be a menace to France. The proportion among young people incidentally was nearly three quarters.” Polls also showed in 1988 that the French preferred the Germans to any of their other neighbors – including the British. Other surveys over the 1980s also demonstrate that the French and Germans had a high degree of mutual confidence across age groups.

As noted already, the Franco-German case shows that given favorable structural conditions during the early postwar period, the successful dynamics of both joint political leadership and NGO networks significantly contributed to the initiation and maturation of reconciliation between the two former adversaries. However, Japan and South Korea, exposed to unfavorable conditions for reconciliation in the early postwar era, had continuous trouble with reconciliation mainly due to the absence (or weakness) of both joint political leadership and reconciliation-promoting NGOs’ activities. While it focuses on the early postwar period in the Franco-German case, this article pays greater attention to the period of the early 1990s-mid 2000s in the Japan-ROK case, because the time period first witnesses real reconciliation efforts initiated by political leaders and NGOs.

Structural Conditions: Although they shared common threats from the Soviet Union, Japan and the ROK faced unfavorable conditions under which it was difficult to seek for bilateral reconciliation in the early postwar period. That is, the Cold War contributed to the rise of Japan as a bulwark against communism, rehabilitating Japan’s prewar elites (e.g., notably Kishi Nobusuke, a member of the wartime cabinet of Hideki Tojo) who had overseen aggressive expansion and colonial exploitation. In other words, the intensification of the Cold War—China’s turn to communism in 1949 and the outbreak of the Korean War in 1950—led to the shift of U.S. policy toward Japan from demilitarization to remilitarization, resulting in the release of many war criminals and their re-entering into Japanese politics. As a result, there emerged Japan’s domestic ideological divisions, which led to the lack of domestic consensus on historical issues required to engage former victims and enemies in constructive dialogue. Former Premier of Singapore Lee Kuan Yew also pointed out this aspect as follows: “the de-nazification process in Europe left no stone unturned. In Asia, by contrast, the communist takeover in mainland China followed by the Korean War prevented a thoroughgoing purge of those really responsible for World War II. And that is why relics from the past have managed to creep back into the mainstream.”

Early Period (1950s-early 1960s): Given this conditional constraint, Japanese political leaders notably lacked incentives for coming to terms with its past in a manner that satisfied South Korea. In the same vein, political leaders in South Korea did not have strong motives for reconciliation with Japan either, because the ROK was then solely dependent upon U.S. support in terms of security and economy. Additionally, political leaders at the time had strong antagonistic feelings toward their counterparts. It is well known that South Korea’s President Syngman Lee held strong antagonistic sentiments against Japan, thus adopting anti-Japanese policies such as the unilateral declaration of “peace line” in 1952. Having unfavorable feelings toward Korea, Japanese Prime Minister Yoshida Shigeru provoked the emotions of Koreans by justifying Japan’s past wrongs in the early postwar era. In this context, the Koreans expected Japan’s sincere apology for its past wrongdoings. Instead of showing public remorse, however, many Japanese political leaders then shared the view that the past policies of the Japanese Empire had been appropriate and justified, and that Japan’s colonial rule even benefited Korea economically.

Unlike the Franco-German case, furthermore, we cannot see any activities of reconciliation-promoting NGO networks between Japan and South Korea during that period. Rather, harsh ideological clashes over historical memories between progressive and nationalistic organizations took place in Japan’s domestic arena. Japan’s nationalistic NGOs such as the Association of Shinto Shrines (Jinja honchō) and the Japan Association of War-bereaved Families (Nihon izokukai) served as a vehicle for solidifying the unapologetic minds and attitudes of Japanese political leaders and the general public. On the political left, on the other hand, the Japan Teachers’ Union (JTU) was opposed to “the public use of the national flag and anthem, the revival of prewar national holidays, and Yasukuni Shrine as a site of national mourning for Japan’s war dead,” which were significant goals of the nationalistic NGOs. As a result, the period of the 1950s-early 1960s falls into the category of “non-reconciliation” between Japan and the ROK on both intergovernmental and popular levels. Except the existence of minimal trade, the two neighbors experienced serious political tensions and heated emotional clashes, thereby failing to establish diplomatic ties.

Middle Period (mid 1960s-1980s): The subsequent time period showed a substantial upsurge in the strength of joint political leadership between Japan and the ROK for mutual cooperation. In terms of NGOs’ activities for reconciliation, however, it was difficult to observe any significant differences from the dynamics in the early postwar era. In the arena of Korean civil society, there were only strong protests of societal actors—e.g., students, laborers and clergies—against authoritarian rulers for democratic transition. In Japan, the ideological clashes between nationalistic and progressive NGOs remained largely unchanged. Given these dynamics of political leaders and NGOs, the middle period witnessed a certain degree of improvement in the intergovernmental and popular reconciliation between the two neighbors. Nevertheless, this change was far from the successful reconciliation shown in the Franco-German case, revolving around a partial reconciliation.

Political leadership changes in the ROK served as a locomotive to escape from a tunnel in which the two countries had great difficulty in normalizing their relationship during the early postwar period. President Syngman Lee, who had consistently maintained antagonistic attitudes toward Japan, resigned from his presidency because of the April Uprising of 1960, which was a revolt against the repression and corruption of his authoritarian regime. Then, Park Jung-Hee, who was an officer in Japan’s imperial army and viewed the Meiji revolution as a model for Korea’s future, took the power by a military coup in 1961 and actively sought for the upgrade of cooperation with Japan. As a result, the two countries established diplomatic ties by signing the Basic Relations Treaty in 1965, despite strong resistance in both nations. The treaty contributed greatly to the increase of economic cooperation between them due to the influx of Japanese capital into South Korea and the rise of mutual trade volume.

The normalization treaty, nonetheless, was not the result of bilateral reconciliation, but rather the product of political and economic calculations. To legitimize his military regime, President Park desperately sought for Japan’s economic support—i.e., $300 million in outright grants and $500 million in loans and credits—through the treaty at the cost of giving up Japan’s sincere apology as well as reparations for its past colonial rule. Japan pursued signing the treaty for market expansion and capital investment in South Korea without showing serious reflections over its past wrongs. To support South Korea’s economic development was also regarded as a means of increasing Japan’s security against the North Korean threat. Hence, although it brought the intergovernmental reconciliation in some sense, the signing of the 1965 normalization treaty later became a seed for historical disputes between the two nations.

Also notable in the 1980s was the joint political leadership between President Chun Doo-Hwan and Prime Minister Nakasone Yasuhiro for elevating the cooperation between Japan and South Korea. In particular, the role of Nakasone was essential to renewing Japan-ROK relations that had experienced serious political tensions caused by the Kim Dae-Jung and Moon Se-Kwang incidents in the 1970s. The Chun regime, established by another military coup in 1980, urgently needed Japan’s economic aid in order to uphold its weak political legitimacy. To finance the Fifth Five Year Socio-economic Plan (1982-86), President Chun asked Japan for a $6 billion loan package in 1981, given the logic that South Korea’s economic development would contribute to the construction of a “bulwark” against communism, helping to defend Japan. Japan was strongly opposed to the security-linked loan request, resulting in the souring of the relationship between the two neighbors. At that time, Nakasone made great efforts to resolve the loan issue, given his desire for improving the relationships with the U.S. and the ROK. An envoy, chosen by Nakasone, arranged compromise over the $4 billion loan through informal talks with the Chun government in Seoul. The final $4 billion loan agreement was concluded at the Chun-Nakasone summit during Nakesone’s official visit to South Korea in January 1983.

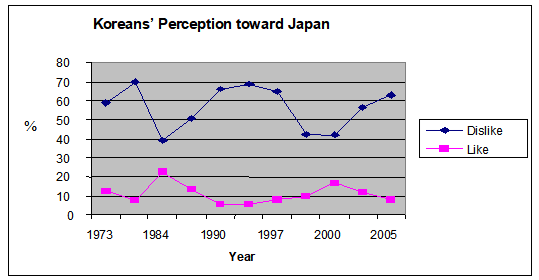

As a consequence, the middle period showed a certain level of upgrade in the intergovernmental relationship between Japan and the ROK owing to the enhanced joint political leadership for bilateral cooperation. The joint leadership was based not on mutual trust, but realpolitik concerns such as security and economy. As noted already, President Park and Chun longed for Japan’s economic help in order to promote Korea’s rapid development, which was the most important basis for their authoritarian ruling. Prime Minister Nakasone also pursued the upgrade of Japan-ROK relations for the purpose of realizing his political goals—to make Japan a normal state and promote Japan’s status in the arena of international politics. At the popular level, there was a meaningful sign for the improvement of popular feelings between the two nations. One notable change was shown after the first postwar summit between Chun and Nakasone in 1983. As shown in Table 2, mutual perceptions (particularly Koreans’ perception toward Japan) improved around 1983, but it did not last long.

Table 2. Koreans’ perception toward Japan (unit: percent)

Year |

1973 |

1978 |

1984 |

1988 |

1990 |

1995 |

1997 |

1999 |

2000 |

2001 |

2005 |

Dislike |

58.6 |

69.9 |

38.9 |

50.6 |

66 |

68.9 |

65 |

42.6 |

42.2 |

56.6 |

63 |

Like |

12.9 |

7.6 |

22.6 |

13.6 |

5.4 |

5.5 |

8 |

9.6 |

17.1 |

12.1 |

8 |

Source: Jungang Daily (1973, 1978); Donga Daily (1984-2005)

Late Period (1990s-mid 2000s): This time period began with significant changes in geopolitical structure and domestic politics in both countries. First, the demise of the Cold War substantially decreased the level of the Soviet threat in Northeast Asia. This change led to the decrease of the U.S. engagement in Japan-ROK relations by weakening the combining mechanism of the anti-communist bloc under the Cold War. Second, the ROK underwent a democratic transition and consolidation after the 1987 June Uprising. Particularly, South Korean democratization opened a door for NGOs’ activities that have affected Japan-ROK relations in both positive and negative ways. Third, Japan’s politics became unstable due to the demise of the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP)’s long rule, the subsequent rise of a coalition cabinet, and the re-emergence of LDP.

Given these changed structural and political conditions, the late period demonstrated a much more complicated dynamics of political leaders and NGOs for international reconciliation between Japan and the ROK. First of all, Japanese Prime Ministers expressed a series of sincere apologies for Japan’s past wrongdoings toward South Korea—i.e., Hosokawa’s candid reference to Japan’s past aggression in 1993 and Murayama’s historic statement of apology in 1995. These actions were derived from the Social Democratic Party (SDP)’s left-wing initiative to reflect on Japan’s past history critically after the breakdown of LDP’s long rule in 1993. Hosokawa said as follows:

During Japan’s colonial rule over the Korean Peninsula, the Korean people were forced to suffer unbearable pain and sorrow in various ways. They were deprived of the opportunity to learn their mother tongue at school, they were forced to adopt Japanese names, forced to provide sex as ‘comfort women’ for Japanese troops, forced to provide labor. I hereby express genuine contrition and offer my deepest apologies for my country, the aggressor’s, acts.

President Kim Dae Jung and Prime Minister Obuchi Keizo, furthermore, declared the new Japan-South Korean partnership for the 21st century in 1998, which included Japan’s first written apology, South Korea’s acceptance of Japan’s apology, and a pledge by both states to move forward. In the 1998 Joint Communique, they also adopted a series of action items to attain the goals of the joint declaration. Particularly stressing the importance of their future relationship, President Kim promised to open South Korea’s mass culture markets to Japan, which had long been taboo in South Korea. Indeed, the 1997 financial crisis in South Korea and the 1998 test-launching of North Korea’s Daepo-dong missile over the sky of Japan contributed to the making of the joint declaration. Just as President Kim needed Japan’s economic assistance to resolve the economic crisis, so Prime Minister Obuchi needed the cooperation with the ROK to deter the North Korean threat. Even though we consider the impact of those realpolitik concerns, the political leaders’ initiatives for reconciliation were an unprecedented and path-breaking action.

Unlike those positive aspects, political leaders in both states also took negative actions for reconciliation between the two neighbors. To gain domestic political support from conservatives, for instance, Japanese Prime Ministers Hashimoto and Koizumi resumed prime ministerial visits to the Yasukuni Shrine that Prime Ministers since Nakasone had avoided. In particular, Koizumi annually visited the Shrine from 2001 to 2006 despite strong opposition from South Korea and China. Korean political leaders also used anti-Japanese sentiment for political purposes. President Kim Young-sam (1993-1998) utilized the territorial dispute over Dokdo/Takeshima as a ploy to gain votes prior to legislative elections in South Korea. In reaction to the territorial conflict, President Roh Moo-hyun was unusually antagonistic toward Japan and declared a “diplomatic war with Japan” just before local elections in mid-April 2005. Hence, the late period was filled with both positive and negative actions for reconciliation taken by political leaders in both countries.

As noted earlier, the ROK democratization opened a new horizon for NGOs’ activities in South Korea. As Korean society democratized, freedom of association made it possible for citizens to create a variety of civic organizations, supporting public concerns over the environment, women’s issues, and human rights. Not until the early 1990s did civic organizations seek to promote bilateral reconciliation between Japan and South Korea. Among them, the most notable NGOs were the Japan-Korea Forum, the Korea-Japan Committee for History Research, and the Korea-Japan History Forum. These NGOs played some roles in furthering the exchange of ideas and cooperative studies, as well as enhancing mutual understanding. In particular, the Japan-Korea forum was held annually after 1993. Participants in the forum came from a variety of fields, including members of legislatures, businesses, the media, culture, and the academic sectors of the two countries. These representatives have views on diverse topics that range from economic, security, and cultural cooperation to the socio-political impact of population movements and generational change in Japan and South Korea. In November 2004, furthermore, scholars of Korea and Japan formed Hanil Yondae 21 (Korea-Japan Solidarity 21) so that they worked together to promote a mutual understanding of regional history. They aimed to advance self-criticism and reflection and to establish regional solidarity between the two neighbors for the twenty-first century. As a result of several years of collaborative work, the regional NGO produced the first-ever East Asian common history guidebook, A History that Opens to the Future: The Contemporary and Modern History of Three East Asian Countries in early 2005.

However, these activities of the reconciliation-promoting NGOs were easily buried under the surface because of active nationalistic NGOs’ movements in both nations. After the demise of LDP’s long reign in 1993, the more progressive SDP took a symbolic step to pass a resolution that emphasized the need to learn from the past. Given this condition, Japan’s history textbooks in the early and mid-1990s reintroduced the factually more actual term “invasion” and incorporated Japanese government’s active role in coercing women from Korea into sexual slavery. In response to this trend, Japanese conservatives created a nationalist organization—the Japanese Society of Composing New History Textbooks (Tsukurukai), which strongly criticized the self-reflective textbooks in the 1990s and published a new right-wing textbook. The Fusosha’s textbook showed a low adoption rate in 2002 due to Japanese NGOs’ active national campaign— the Japan School Teachers’ Association, Children and National Network 21 for Textbooks, and Peace Boat 21. Nevertheless, the right-wing textbook became a seed for chronic historical disputes between Japan and South Korea because the Japanese Ministry of Education oversees history textbooks every four years.

Although they played crucial roles in correcting historical facts, a variety of NGOs in South Korea also served as a catalyst to spotlight conflictual aspects in Japan-ROK relations, particularly historical problems such as comfort women, forced laborers, and history textbooks. To request Japan’s official apology and reparations for comfort women, the Korean Council (for the Women Drafted for Military Sexual Slavery by Japan), organized in 1990, has continuously issued numerous statements and conducted regular “Wednesday Demonstrations” in front of the Japanese Embassy in Seoul. Whenever Japan renewed its original position on history agendas, many NGOs related to Dokdo led anti-Japanese demonstrations. Prior to the 2005 historical dispute between Japan and the ROK, a variety of Councils organized by many NGOs strongly asked the Roh regime to resolve historical problems, including reparations for forced laborers during Japan’s colonial rule and the inspection of collaborations for Japanese imperialism. Unlike previous time periods, therefore, President Roh had to face political pressures from those NGOs and took a tougher stance toward Japan in the historical dispute.

Given this complicated dynamics of political leaders and NGOs, the late period seemingly showed significant improvements in both intergovernmental and popular relationships between Japan and South Korea. First, the promotion of security cooperation was notable in terms of institutionalized discussions on security from the working level to the ministerial level, and an increasing array of military exchanges and joint exercises. After director-general-level security consultations were initiated in 1997, the two neighbors established communication hotlines between the Korean Ministry of National Defense and the Japanese Defense Agency, as well as between their respective air and naval components in 1999. Just as Korean and Japanese air force chiefs held successful meetings in Seoul, so the two sides’ Navies conducted unprecedented joint exercises and goodwill port calls in the same year.

Second, compared with previous time periods, the late period witnessed an explosive upsurge in trade and tourism between Japan and South Korea. As illustrated in Table 3, in 1984 the total volume of trade between the two countries was about twelve billion dollars. It increased to thirty billion in 1993 and to seventy-two billion dollars in 2005. As Table 4 details, the number of Korean visitors to Japan dramatically increased from 144,424 in 1982, to 321,526 in 1988, to 1,051,865 in 1994, and to 1,569,176 in 2004. The number of Japanese visitors to South Korea, compared with the period in the late 1970s, doubled during the 1980s and quadrupled during the 1990s and 2000s.

Table 3. Trade of South Korea with Japan (unit: million dollars)

Year |

1984 |

1987 |

1990 |

1993 |

Export |

4,602 |

8,437 |

12,638 |

11,564 |

Import |

7,640 |

13,657 |

18,574 |

20,016 |

Year |

1996 |

1999 |

2002 |

2005 |

Export |

15,767 |

15,862 |

15,143 |

24,027 |

Import |

31,449 |

24,142 |

29,856 |

48,403 |

Source: www.mofat.gov.kr (Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade)

Table 4. Number of Korean and Japanese Visitors in Japan and South Korea

Year |

1976 |

1979 |

1982 |

1985 |

1988 |

Korean |

60,217 |

77,156 |

144,424 |

166,523 |

321,526 |

Japanese |

521,128 |

649,707 |

518,013 |

638,941 |

1,124,149 |

Year |

1991 |

1994 |

1997 |

2000 |

2004 |

Korean |

914,155 |

1,051,865 |

1,126,573 |

1,100,939 |

1,569,176 |

Japanese |

1,455,090 |

1,644,097 |

1,676,434 |

2,472,054 |

2,443,070 |

Source: www.knto.or.kr (Korea National Tourism Organization)

Third, cultural exchanges advanced due to the ROK abolition of the ban on the import of Japanese popular culture in 1998. As an example, it is no longer surprising to hear that many young students in South Korea are learning Japanese to play Japanese computer games and see Japanese cartoons and movies. As shown in Table 5, the percentage of Korean high school students studying Japanese as their second foreign language dramatically increased from 29.3% in 1991 to 61.2% in 2005. These figures surpass the percentage of Korean students learning other languages such as German and Chinese. Furthermore, the popularity of Korean celebrities in Japan is remarkable. Korean actors and singers are leading an unprecedented Korea boom in Japan called the “Hanryu” or “the Korean Wave.” Even despite the 2005 Japan-ROK diplomatic flare-up over textbooks and the disputed island, Japanese fans continued visiting Korea to see Korean actors. The two nations also successfully co-hosted the 2002 World Cup Soccer Games.

Table 5. Second Foreign Language Studies of Korean High School Students

(unit: percent)

Year |

German |

French |

Spanish |

Chinese |

Japanese |

1991 |

42.7 |

23.8 |

1.1 |

3.1 |

29.3 |

1994 |

42.8 |

25.1 |

0.7 |

4.3 |

27.1 |

1997 |

41.1 |

25.2 |

1.5 |

5.8 |

25.7 |

2000 |

35.9 |

22.5 |

1.4 |

9.1 |

31.1 |

2001 |

30.2 |

18.8 |

1.4 |

10.5 |

39.1 |

2002 |

24.6 |

15.8 |

1.2 |

12.9 |

45.4 |

2003 |

16.2 |

10.9 |

1.1 |

17.0 |

54.7 |

2005 |

8.2 |

6.8 |

1.0 |

22.4 |

61.2 |

Source: http://std.kedi.re.kr (Korean National Center for Education Statistics & Information)

During the late period, nevertheless, Japan and South Korea failed to reach the level of the successful reconciliation shown in the Franco-German case, as the complicated dynamics of political leaders and NGOs raised and intensified historical disputes between the two neighbors. The clashes often resulted in ambassador recalling, which was an action regarded as the highest level of diplomatic protests, and the suspension of shuttle diplomacy between top leaders, thereby disrupting the enhanced intergovernmental cooperation. The initiative taken by Kim and his counterpart Obuchi was unprecedented in postwar Japan-ROK relations, but the promising new overture of bilateral ties was seriously undermined due to the 2001 history textbook controversy and the Japanese political leaders’ visit to the Yasukuni Shrine. By the same token, historical disputes further aggravated popular feelings, particularly Koreans’ perceptions toward Japan. As Figure 1 demonstrates, historical disputes in 2001 and 2005 significantly worsened Koreans’ feelings toward Japan in the period of 2001-2005, despite the unprecedented Kim-Obuchi reconciliation initiatives. However, Table 6 shows an impressive outcome that Japanese intimate feelings toward the ROK surpassed the “no intimacy rate” by 1999 and maintained the pattern persistently.

Figure 1. Koreans’ Perception toward Japan

Source: Jungang Daily (1973, 1978); Donga Daily (1984-2005)

Table 6. Japanese perception toward South Korea (unit: percent)

Year |

1978 |

1985 |

1989 |

1993 |

1996 |

1999 |

2001 |

2003 |

2004 |

2005 |

No Intimacy |

45.2 |

45.2 |

52.2 |

51.8 |

60.6 |

46.9 |

45.5 |

41.0 |

39.2 |

44.3 |

Intimacy |

40.1 |

45.2 |

40.7 |

43.4 |

35.8 |

48.3 |

50.3 |

55.0 |

56.7 |

51.1 |

Source: Japanese Cabinet

This article sought to answer the two questions over the motives for reconciliation between the former adversary states and different processes/outcomes in their reconciliation efforts. In both cases, it was certain that the former adversaries sought for bilateral reconciliation based on conditional factors and realpolitik concerns such as security and economy. However, the dynamics of political leaders and NGOs played central roles in differentiating the reconciliation processes and outcomes in the two dyadic relationships. In the Franco-German case, there was not only the strong joint political leadership for reconciliation, but also the positive dynamics of pro-reconciliation NGOs in the early postwar era. Although France and Germany experienced some conflicts of interests, they continuously maintained and nurtured their reconciled relationship on both intergovernmental and popular levels. On the other hand, Japan and the ROK showed no joint political leadership for reconciliation and reconciliation-promoting NGOs in the early postwar era. Even in the late period, the negative dynamics of political leaders and NGOs in both nations often disrupted the intergovernmental and popular relationships improved by their positive dynamics. Therefore, the two neighbors revolved around a partial reconciliation until the mid-2000s.

The article combined two variables—i.e., political leaders and NGOs—and designed an alternative reconciliation model to explain the degree of reconciliation between former enemy states in a systematic way. The newly created analytical model contributes to the scholarly literature of the two dyadic relationships in three important ways. First, focusing on the roles of the domestic agents in the reconciliation process promotes analytical rigor, thus going beyond historical narratives by providing systematic explanations for the two cases. Second, it complements the weaknesses of the dominant historical perception approach through explaining the cross-temporal variations (both ups and downs) in the degrees of reconciliation. Third, it enables us to overcome a sense of structural determinism that solely focuses on the effects of U.S. policies on the relationships.

In addition, this comparative study poses an important question for the real world. The bilateral reconciliation between Japan and South Korea, who share common values of democracy and free markets, is a necessary condition for establishing a stable regional order in Northeast Asia. Similarly, the Franco-German reconciliation has contributed to European integration and peacekeeping. Without a successful reconciliation between Japan and South Korea, building a peaceful Northeast Asian community that can rise above historical and ideological antagonism would be difficult. Moreover, in the long run, the international reconciliation between Japan and South Korea can play a critical role in the process of the future reunification between South and North Korea, which will require a great deal of joint support from Japan and South Korea. In this regard, how political leaders and NGOs in both nations contribute to Japan-ROK reconciliation will be an important criterion for the construction of a stable and peaceful Northeast Asian community.

Principal References

Ackermann, Alice, “Reconciliation as a Peace-Building Process in Postwar Europe: The Franco-German Case,” Peace & Change, vol. 19, No. 3, (July 1994)

Bridges, Brian, Japan and Korea in the 1990s: From Antagonism to Adjustment (The Cambridge University Press, 1993)

Cha, Victor D., Alignment Despite Antagonism: The US-Korea-Japan Security Triangle (Stanford University Press, 1999)

Cheong, Sung-Hwa, The Politics of Anti-Japanese Sentiment in Korea: Japanese-South Korean Relations Under American Occupation, 1945-1952 (Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 1991)

Crocker, David A., “Reckoning with Past Wrongs: A Normative Framework,” Ethics & International Affairs, (1999)

Farquharson, John E., and Holt, Stephen C., Europe from Below: an assessment of Franco-German popular contacts (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1975)

Feldman, Lily Gardner, “The principle and practice of ‘reconciliation’ in German foreign policy: relations with France, Israel, Poland and the Czech Republic,” International Affairs vol. 75, No. 2 (1999)

Friend, Julius W., The Linchpin French-German Relations, 1950-1990 (New York: Praeger, 1991)

Funabashi, Yoichi, eds., Reconciliation in the Asia-Pacific (United States Institute of Peace Press, 2003)

He, Yinan, “Overcoming Shadows of the Past: Post-Conflict Interstate Reconciliation in East Asia and Europe,” (Ph.D. diss., MIT 2004)

Hendriks, Gisela and Morgan, Annette, The Franco-German Axis in European Integration (Edward Elgar Publishing, 2001)

Horvat, Andrew, “Overcoming the Negative Legacy of the Past: Why Europe is a Positive Example for East Asia,” Brown Journal of World Affairs, vol. XI, Issue 1, (Summer/Fall 2004)

Kim, Sunhyuk, The Politics of Democratization in Korea: The Role of Civil Society (University of Pittsburgh Press, 2000)

Krotz, Ulrich, “Parapublic Underpinnings of International Relations: The Franco-German Construction of Europeanization of a Particular Kind,” European Journal of International Relations, vol. 13, No. 3, 2007

Lee, Chong-Sik, Japan and Korea: The Political Dimension (Hoover Institution Press, 1985)

Lee, Won-deog, Han-Il Kwagŏsa ch´ŏri ŭi wŏnjŏm: Ilbon ŭi chŏnhuch´ŏri oegyo wa Han-Il hoedam (Starting Point for Settlement of Korea-Japan Past History), (Seoul: Seoul National University Press, 1996)

Lind, Jennifer, “Apologies in International Politics” Paper prepared for the International Relations Workshop, Yale University, (Spring 2007)

Moon, Chung-in and Suh, Seung-won, “Security, Economy, and Identity Politics: Japan-South Korean Relations under the Kim Dae-jung Government,” Korea Observer, vol. 36, No. 4, (Winter 2005)

Park, Cheol Hee, “Historical Memory and the Resurgence of Nationalism: A Korean Perspective” in Toshi Hasegawa and Kuzu Togo, eds., East Asia’s Haunted Past (New York: Palgrave, 2008)

----------------- “Han-Il Galdung ŭi Panungjuk Chokbal kwa Wonronjuk Daeung ŭi Kujo (Responsive Eruption of Korea-Japan Conflict and Structure of Fundamental Reaction),” Hanguk Chungchi Oegyosa Nonchong, vol. 29, No. 2, 2008

Sheetz, Mark Stephen, “Continental Drift: Franco-German Relations and the Shifting Premises of European Security,” (Ph.D. diss., Columbia University, 2002)

Shin, Gi-Wook, Park, Soon-Won and Yang, Daqing, eds., Rethinking Historical Injustice and Reconciliation in Northeast Asia: The Korean Experience (Routledge, 2007)

Willis, F. Roy, France, Germany, and the New Europe, 1945-1997 (Stanford University Press, 1968)

Yoon, Tae-Ryong, “Fragile Cooperation: Net Threat Theory and Japan-Korea-U.S. Relations,” (Ph.D. diss., Columbia University, 2006)

------------------ “Learning to Cooperate Not to Cooperate: Bargaining for the 1965 Korea-Japan Normalization,” Asian Perspective, vol. 32, No. 2, 2008

Wakamiya, Yoshibumi, The Postwar Conservative View of Asia: How the Political Right Has Delayed Japan’s Coming to Terms with its History of Aggression in Asia (LTCB International Library Foundation, 1999)

* This work was supported by the Korea Foundation 2008 Fellowship for Field Research.

Jennifer M. Lind, “Sorry States: Apologies in International Politics” (Ph.D. diss., MIT, 2004), pp. 246-50.

F. Roy Willis, France, Germany, and the New Europe, 1945-1967 (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1968); Julius W. Friend, The Linchpin: French-German Relations, 1950-1990 (New York: Praeger, 1991); Stephen A. Kocs, Autonomy or Power? The Franco-German Relationship and Europe’s Strategic Choices, 1955-1995 (Westport, Conn.: Praeger, 1995).

Chong-Sik Lee, Japan and Korea: The Political Dimension (Hoover Institution Press, 1985), pp. 1-3; Brian Bridges, Japan and Korea in the 1990s: From Antagonism to Adjustment (Cambridge University Press, 1993), pp. 6-9.

Yaacov Bar-Siman-Tov, eds., From Conflict Resolution to Reconciliation (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004); Daniel Philpott, “Beyond Politics as Usual: Is Reconciliation Compatible with Liberalism,” in Daniel Philpott, eds., The Politics of Past Evil: Religion, Reconciliation, and the Dilemmas of Transitional Justice (Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 2006), pp. 11-14.

David A. Crocker, “Reckoning with Past Wrongs: A Normative Framework,” Ethics & International Affairs (1999), pp. 60-61.

Yinan He, “Overcoming Shadows of the Past: Post-Conflict Interstate Reconciliation in East Asia and Europe” (Ph.D. diss., MIT 2004), pp. 13-16.

Yoichi Funabashi, eds., Reconciliation in the Asia-Pacific (United States Institute of Peace Press, 2003); He, “Overcoming Shadows of the Past”; Alice Ackermann, “Reconciliation as a Peace-Building Process in Postwar Europe: The Franco-German Case,” Peace & Change, vol. 19, No. 3 (July 1994); Lily Gardner Feldman, “The principle and practice of ‘reconciliation’ in German foreign policy: relations with France, Israel, Poland and the Czech Republic,” International Affairs vol. 75, No. 2 (1999); Seung-Hoon Heo, “Reconciliation Hereditary Enemy States: Franco-German and South Korean-Japanese Relations in Comparative Perspective,” The Journal of International Policy Solutions, vol. 8, (Winter 2008).

He, “Overcoming Shadows of the Past,” pp. 57-59.

Lee, Japan and Korea; Kong Dan Oh, “Japan-Korea Rapprochement: A Study in Political, Cultural, and Economic Cooperation in the 1980’s” (Ph.D. diss., University of California at Berkeley, 1986); Sung-Hwa Cheong, The Politics of Anti-Japanese Sentiment in Korea: Japanese-South Korean Relations Under American Occupation, 1945-1952 (Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 1991); Bridges, Japan and Korea in the 1990s.

Victor D. Cha, Alignment Despite Antagonism: The US-Korea-Japan Security Triangle (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1999).

Willis, France, Germany, and the New Europe; Haig Simonian, The Privileged Partnership: Franco-German Relations in the European Community, 1969-1984 (Clarendon Press, 1985).

David P. Calleo and Eric R. Staal, ed., Europe’s Franco-German Engine (Washington DC: Brookings Institution Press, 1998); Douglas Webber, ed., The Franco-German Relationship in the European Union (London: Routledge, 1999); Alistair Cole, Franco-German Relations (Pearson Education, 2001); Gheciu, Alexandria, “Security Institutions as Agents of Socialization? NATO and the New Europe,” International Organization, vol. 59, No. 3 (Fall 2005).

Julius W. Friend, The Linchpin French-German Relations, 1950-1990 (New York: Praeger, 1991); Gisela Hendriks and Annette Morgan, The Franco-German Axis in European Integration (Edward Elgar Publishing, 2001).

John E. Farquharson and Stephen C. Holt, Europe from Below: an assessment of Franco-German popular contacts, (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1975); Lily Gardner Feldman, “The role of non-state actors in Germany’s foreign policy of reconciliation: catalysts, complements, conduits, or competitors?” in Anne-Marie Le Gloannec eds., Non-State Actors in International Relations: The Case of Germany (Manchester University Press, 2007); Ulrich Krotz, “Parapublic Underpinnings of International Relations: The Franco-German Construction of Europeanization of a Particular Kind,” European Journal of International Relations, vol. 13, No. 3, (2007).

Mark Stephen Sheetz, “Continental Drift: Franco-German Relations and the Shifting Premises of European Security” (Ph.D. diss., Columbia University 2002), pp. 381-83.

Cathy Gormely-Heenan, Political Leadership and the Northern Ireland Peace Process: Role, Capacity and Effect (Palgrave Macmillan, 2007), pp. 6-7.

Feldman, “The role of non-state actors,” pp. 17-20.

Andrew Horvat, “Overcoming the Negative Legacy of the Past: Why Europe is a Positive Example for East Asia,” Brown Journal of World Affairs, vol. XI, Issue 1, (Summer/Fall, 2004), p. 141.

Hendriks and Morgan, The Franco-German Axis, p. 5.

Friend, The Linchpin, pp. ix-x.

John W. Young, France, the Cold War and the Western Alliance, 1944-1949: French Foreign Policy and Postwar Europe (New York: St. Martin’s, 1990); Willis, The French in Germany (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1962).

Willis, France, Germany, chapter 2; Friend, The Linchpin, chapter 1; David A. Meier, “French-German Relations: The Strasbourg-Kehl Encounter, 1945-55,” European Review of History, vol. 11, No. 1, (2004).

Farquharson and Holt, Europe from Below.

Willis, France, Germany, p. 103.

Farquharson and Holt, Europe from Below, p. 89.

Friend, The Linchpin, pp. 35-40.

Kocs, Autonomy or Power? p. 42: “Under the treaty terms, the French president was to meet with the German chancellor at least twice a year, and the two foreign ministers to meet at least once every three months. The two governments were to consult each other, prior to any decision, on all important questions of foreign policy…with a view to arriving…at a similar position.”

Friend, The Linchpin, pp. 41-42.

Krotz, “Parapublic Underpinnings of International Relations,” p. 392.

Bar-Siman-Tov, eds. From Conflict Resolution to Reconciliation, p. 33.

Farquharson and Holt, Europe from Below, pp. 150-53.

Ackermann, “Reconciliation as a Peace-Building Process in Postwar Europe,” pp. 240-41.

Alfred Grosser, French Foreign Policy under De Gaulle (Boston: Little Brown, 1967), p. 6.

Farquharson and Holt, Europe from Below, p. 188.

Jennifer M. Lind, “Apologies in International Politics,” International Relations Workshop (Yale University, Spring 2007), p. 34.

Donald J. Puchala, “Integration and Disintegration in Franco-German Relations, 1954-1965,” International Organization, vol. 24, No. 2, (Spring 1970), pp. 188-89.

Friend, The Linchpin, pp. 51-77.

Farquharson and Holt, Europe from Below, pp. 155-59.

Christian Science Monitor (Boston, MA), January 22, 1988, (Friday), international, p. 10.

Ulrich Krotz, “Structure as Process: The Regularized Intergovernmentalism of Franco-German Bilateralism,” 2002 Working Paper in the Program for the Study of Germany and Europe, p. 28.

Feldman, “The principle and practice of ‘reconciliation’ in German foreign policy,” pp. 345-46

Ackermann, “Reconciliation as a Peace-Building Process in Postwar Europe,” p. 243.

Krotz, “Structure as Process, pp. 14-22.

Ibid, p. 14.

Max Otte and Jurgen Greve, A Rising Power? German Foreign Policy in Transformation, 1989-1999 (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2000), p. 75

Farquharson and Holt, Europe from Below, pp. 188-91.

Christian Science Monitor (Boston, MA), January 22, 1988, Friday, international, p. 10.

Friend, The Linchpin, pp. 42-43.

Andrew Horvat, “A strong state, weak civil society, and Cold War geopolitics” in Shin, Park, and Yang, eds., Rethinking Historical Injustice and Reconciliation, pp. 220-221; Tae-Ryong Yoon, “Fragile Cooperation: Net Threat Theory and Japan-Korea-U.S. Relations” (Ph.D. diss., Columbia University, 2006), pp. 46-47.

Herbert P. Bix, Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan (New York: HarperCollins, 2000), p. 652.

Ian Buruma, “Commentary” in Andrew Horvat and Gebhard Hielscher, eds, Sharing the Burden of the Past: Legacies of War in Europe, America and Asia (Tokyo: The Asia Foundation/Friedrich Ebert Stiftung, 2003), p. 140: The Japanese left sticking to the pacifist constitutions strongly supports the fact that Japan should not become a military power based on the past atrocious and horrible experiences of World War II. On the other hand, by changing the constitution the Japanese right wanted Japan to regain the sovereign right to wage war, seeking to minimize Japan’s past wrongdoings.

Asahi Shimbun, November 22, 1994. Quoted in Wakamiya Yoshibumi, The Postwar Conservative View of Asia: How the Political Right Has Delayed Japan’s Coming to Terms with its History of Aggression in Asia, (LTCB International Library Foundation, 1999), p 49.

Cheong, The Politics of Anti-Japanese Sentiment in Korea.

Lee, Japan and Korea, pp. 23-31; Wakamiya Yoshibumi, The Postwar Conservative View of Asia, Chapter 1.

Franziska Seraphim, War Memory and Social Politics in Japan, 1945-2005 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2006), Introduction: Those NGOs focused their energy on resurrecting features of the wartime system—the historical continuity of the emperor as the spiritual essence of all Japanese and the appropriate commemoration of millions of military dead at Yasukuni Shrine—that occupation policies had dismantled.

Ibid., p. 9.

Lee, Japan and Korea, pp. 23-31

Sunhyuk Kim, The Politics of Democratization in Korea: The Role of Civil Society (University of Pittsburgh Press, 2000), pp. 137-38.

Sunhyuk Kim, The Politics of Democratization in Korea, pp. 137-38.

Cha, Alignment Despite Antagonism, pp. 59-168; Lee, Japan and Korea, pp. 43-104; Yoon, “Fragile Cooperation” Chapter 4.

To understand the detailed processes in making the treaty, see Won-deog Lee’s book, Han-Il Kwagŏsa ch´ŏri ŭi wŏnjŏm: Ilbon ŭi chŏnhuch´ŏri oegyo wa Han-Il hoedam (Starting Point for Settlement of Korea-Japan Past History), (Seoul: Seoul National University Press, 1996) and Lee, Japan and Korea, pp. 44-53.

Tae-Ryong Yoon, “Learning to Cooperate Not to Cooperate: Bargaining for the 1965 Korea-Japan Normalization,” Asian Perspective, vol. 32, No. 2, 2008, pp. 59-91.

Lee, Japan and Korea, pp. 81-85: Kim Dae Jung was kidnapped in Japan by the Korean Central Intelligence Agency (KCIA) in 1973. And, a North Korean resident (Moon Se-Kwang) of Japan attempted to assassinate Park Jung Hee in August 1974.

Bridges, Japan and Korea in the 1990s, pp. 14-15.

Isa Ducke, Status Power: Japanese Foreign Policy Making toward Korea (New York and London: Routledge, 2002), pp. 88-89.

Cha, Alignment Despite Antagonism, p. 75; Lee, Japan and Korea, p. 110: in addition, Japan and South Korea demonstrated a minimal state of security cooperation, which included Japan’s confirmation of the “Korea Clause (meaning that the security of the ROK was essential to Japan’s own security),” and Japanese high-ranking military officials’ visits to Seoul.

Won-deog Lee, Han-Il kwangye ŭi kuchochŏnhwan kwa jaengchŏmhyunhwang ŭi punsŏk (Structural Changes of Korea-Japan Relations and Analysis of Current Issues), Ilbon Yŏngu Nonchong, vol. 14, 2001, pp. 34-36.

Larry Diamond and Doh-chull Shin, eds., Institutional Reform and Democratic Consolidation in Korea (Hoover Institution Press, 2000) and Larry Diamond and Byung-kook Kim, eds., Consolidating Democracy in South Korea (Lynne Rienner Publishers, Inc. 2000): A procedural democracy was established through the set-up of direct presidential elections to be held every five years from December 1987. Civil liberties improved due to the abolition of various laws such as the Basic Press Law and a number of labor laws. The former was enacted in 1980 to systemically censor the press and the latter served as a means of restricting the exercise of labor rights. The influence of the military on Korean politics and society dramatically decreased following the drastic reforms performed by Kim Young-sam (1993-1997), the first civilian president since 1961. The peaceful transition of power to an opposition party led by longtime dissident Kim Dae-jung occurred in 1998.

Cheol Hee Park, “Historical Memory and the Resurgence of Nationalism: A Korean Perspective” in Toshi Hasegawa and Kuzu Togo, eds., East Asia’s Haunted Past (New York: Palgrave, 2008), Chapter 10.

Asahi Shimbun, November 7, 1993. Quoted in Jennifer Lind, “Sorry States: Apologies in International Politics,” unpublished paper for the annual meeting of the APSA, Washington D.C., 2005, p. 23.

Wakamiya, The Postwar Conservative View of Asia, pp. 256-58.

Chung-in Moon and Seung-won Suh, “Security, Economy, and Identity Politics: Japan-South Korean Relations under the Kim Dae-jung Government,” Korea Observer, vol. 36, No. 4, (Winter 2005), p. 564.

Ibid., pp. 569-73.

Cheong, The Politics of Anti-Japanese Sentiment in Korea, p. 138; Victor Cha, “Hypotheses on History and Hate in Asia: Japan and the Korean Peninsula,” in Reconciliation in the Asia-Pacific, eds., Yoichi Funabashi (Institute of Peace Press, 2003), p. 50: previous leaders also used the tactic. Given his shaky power base in postwar Korea, President Syngman Rhee (1948-60) made efforts to manipulate popular anti-Japanese feelings in order to stabilize his regime. The Chun Doo-hwan regime (1980-87) also strived to stir up anti-Japanese sentiments for the purpose of distracting people’s attention away from the regime’s military origins and gaining domestic legitimacy.

Park, “Historical Memory and the Resurgence of Nationalism,” pp. 18-21.

Sunhyuk Kim, “Civil Society in Democratizing Korea,” in Samuel S. Kim, eds., Korea’s Democratization (Cambridge University Press, 2003), pp. 84-85.

Online at http://www.jcie.or.jp/thinknet/forums/Korea-Japan/

Shin, Park, and Yang, eds., Rethinking Historical Injustice and Reconciliation, p. 256.

David Hundt and Roland Bleiker, “Reconciling Colonial Memories in Korea and Japan” Asian Perspective, vol. 31, No. 1, 2007, p. 73-75.

Moon and Suh, “Security, Economy, and Identity Politics,” pp. 591-92.

Online at http://www.womenandwar.net/menu_02.php

ChungAng Daily, February 24, 2005; Donga Daily, April 6, 2005: The following three actions ignited the dispute. On Feb 23, 2005, a Japanese prefectural assembly decided to enact a bill designating February 22 as “Takeshima (Dokdo’s Japanese name) Day.” On the same day, the Japanese ambassador to South Korea stated Japan’s sovereignty over Dokdo at a press conference for the foreign media held in Seoul. On April 6, 2005, the Japanese government announced the approval of new history textbooks that contain Japan’s claims of sovereignty over Dokdo but exclude past wrongs such as comfort women and forced laborers.

Cheol Hee Park, “Han-Il Galdung ŭi Panungjuk Chokbal kwa Wonronjuk Daeung ŭi Kujo (Responsive Eruption of Korea-Japan Conflict and Structure of Fundamental Reaction),” Hanguk Chungchi Oegyosa Nonchong, vol. 29. No. 2, (February 2008), p. 335-39.

Cha, “Hypotheses on History and Hate in Asia,” p. 49.

Victor Cha, “Japan-ROK Relations: Rooting the Pragmatic,” vol. 1, No. 1, 2nd Quarter, (July 1999). Online at http://www.csis.org/pacfor/ccejournal.html

Chosun Daily, March 18, 2005.

Source: http://home.sogang.ac.kr/sites/iias/iias02/Lists/b6/Attachments/32/27th_InternationalReconciliationinthePostwarEra.doc

Web site to visit: http://home.sogang.ac.kr/

Author of the text: indicated on the source document of the above text

If you are the author of the text above and you not agree to share your knowledge for teaching, research, scholarship (for fair use as indicated in the United States copyrigh low) please send us an e-mail and we will remove your text quickly. Fair use is a limitation and exception to the exclusive right granted by copyright law to the author of a creative work. In United States copyright law, fair use is a doctrine that permits limited use of copyrighted material without acquiring permission from the rights holders. Examples of fair use include commentary, search engines, criticism, news reporting, research, teaching, library archiving and scholarship. It provides for the legal, unlicensed citation or incorporation of copyrighted material in another author's work under a four-factor balancing test. (source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fair_use)

The information of medicine and health contained in the site are of a general nature and purpose which is purely informative and for this reason may not replace in any case, the council of a doctor or a qualified entity legally to the profession.

The texts are the property of their respective authors and we thank them for giving us the opportunity to share for free to students, teachers and users of the Web their texts will used only for illustrative educational and scientific purposes only.

All the information in our site are given for nonprofit educational purposes